Реферат: People of Ancient Britain History of Britain

Although there is almost no evidence for such а thing, we can be sure that many of the ancient British remained. Certainly they had little in common with the newcomers, and failed, for example, to convert them to Christianity. But it does not seem likely that the whole native population was killed or driven away. Many of the British must have become slaves of the Anglo-Saxons, and many British women must have borne the children of Saxon fathers. But as far as history is concerned, in the regions settled by the Anglo-Saxons the old British society ceased to exist.

Прибытие англосаксов

Германцы, захватившие Британию, которым суждено было стать англичанами, прибыли из северо-западной Европы, области между устьем Рейна и Балтийским морем. По стандартам римлян они были нецивилизованными людьми. Они никогда не были под властью римлян, и когда они достигли Англии, они были поражены римскими зданиями. Только раса гигантов, думали они, могла бы построить их. Они избегали городов, предпочитая свои собственные, более простые поселения.

Германцы, захватившие Британию, которым суждено было стать англичанами, прибыли из северо-западной Европы, области между устьем Рейна и Балтийским морем. По стандартам римлян они были нецивилизованными людьми. Они никогда не были под властью римлян, и когда они достигли Англии, они были поражены римскими зданиями. Только раса гигантов, думали они, могла бы построить их. Они избегали городов, предпочитая свои собственные, более простые поселения.

Сначала англосаксы прибывали малыми группами. Позже, полюбив страну, они начали прибывать большими отрядами, и стали перемещаться внутрь страны, найдя путь к сердцу Англии, к Темзе и другим рекам. Англия, которая предстала перед ними, не многим была похожа на Англию наших дней. Судя по англосаксонской поэзии, это было мрачное, холодное место. Тернистые леса и бесплодные пустоши покрывали многие земли, болота и топи покрывали и того больше. Реки не были аккуратно заключены в пределах своих берегов, а растекались по полям. Медведи, волки и дикие боровы бродили по лесам. В Сомерсете водились пеликаны, а в Суррее золотые орлы.

В самый пиковый момент иммиграции, в 6-ом веке, количество англо-саксонских отрядов насчитывало многие сотни, возможно тысячи. Но это никогда не было массовой миграцией. Имело место несколько больших сражений, но англосаксы не получали землю без применения силы.

Мало того, что они воевали с британцами, они воевали между собой. Саксы и Англы воевали за владение Центральными графствами, саксы и юты за Суррей и Гэмпшир. Постепенно, семейства соединялись, чтобы образовать более крупные, более сильные племена, а затем королевства. Примерно к 600-ому году, вновь прибывшие контролировали всю Англию кроме самого северо-запада и юго-запада, вдобавок к этому и юго-восток Шотландии; но они не овладели Уэльсом.

Что же, тем временем, происходило с британцами-кельтами? То здесь, то там археологи находят свидетельство того, что эти два народа жили бок о бок – или же умирали бок о бок – так в Йорке гробы Римского стиля были погребены рядом с германскими урнами. Все же есть некоторые признаки римского или же кельтского влияния на англосаксов в Англии. Британцы отступали назад, в более отдаленные и гористые части Британии, в которые англосаксы, как и римляне до них, почти не проникли.

Хотя тому нет почти никаких свидетельств, мы можем быть уверенными, что многие из древних британцев остались. Конечно, они имели немного общего со вновь прибывшими, и не смогли, например, обратить их в христианство. Но не кажется вероятным, что всё коренное население было уничтожено или изгнано. Многие из британцев должно быть стали рабами англосаксов, а многие британские женщины должно быть родили детей от англосаксонских отцов. Но с точки зрения истории в областях, заселенных англосаксами, старое британское общество перестало существовать.

The England of the Anglo-Saxons History of Britain (историяБритании)

Anglo-Saxon England settled into a pattern of seven kingdoms. The three largest, Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex eventually came to dominate the country, each at different times. First it was Northumbria (the only time in English history when the centre of power has been in the north). Northumbria stretched as far as Edinburgh and for a time included part of the kingdom of Strathclyde, in south-west Scotland.

Offa's Dyke

During the 8th century, Northumbrian leadership was replaced by the midlands kingdom of Mercia. The greatest of Mercian kings, Offa (757-796), corresponded with the mighty Charlemagne, emperor of the Franks; he minted his own coins - the first nationwide currency since Roman times. He is remembered also as the builder of Offa's Dyke (ров), an earth rampart over 190 kilometres long which marked the border of Mercia with Wales. It can still be seen, but it was much higher in Offa's time.

On his coins, Offa called himself 'king of the English', and his power stretched far enough for him to have a rebellious king of East Anglia beheaded, and to give estates to his subjects in Sussex. He even had some influence in Northumbria.

However, neither Northumbria nor Mercia succeeded in making their kings the rulers of all England. That honour was to fall to the House of Wessex, made great by King Alfred.

However, neither Northumbria nor Mercia succeeded in making their kings the rulers of all England. That honour was to fall to the House of Wessex, made great by King Alfred.

But what was this office of kingship, and how did it work in Anglo-Saxon England?

The idea of kingship was not invented in England. The Anglo-Saxons knew it in Germany. Kings grew from simple tribal chiefs who were leaders successful in war, and therefore conquest of land. As time went by, the king became a grander, more exalted figure, and when England became Christian again in the 7th century reverence for kingship was encouraged by the Church.

The king was elected; he did not gain his crown by right of inheritance. Or not at first. In time it became the custom to elect a member of the royal family. Still the king's power was not total. He ruled with the advice of his council - the great men of the kingdom. He had no permanent capital and was always on the move. It must have been quite difficult for visitors hoping for a royal interview to track him down.

The later Anglo-Saxon kings received a constant stream of visitors, from overseas and from other parts of Britain. In 973 King Edgar was visited by no less than eight sub-kings at the same time. They manned the oars of his boat as a gesture of loyalty.

Such visitors brought expensive gifts, or tributes. But for his regular income the king relied on the profits of his own estates. which were large and widely scattered, and. on rent, usually paid 'in kind' - i.e. as goods, not cash. Receipts from tolls of various kinds and fines from the law courts added something. His subjects gave him free labour and military service: in an emergency that meant every male who could swing a sword. Special expenses, like bribing the Vikings not to attack, were met by special taxes, and various persons or places owed special duties to the king. Norwich, for example, supplied a bear and six dogs for the sport of bear-baiting.

Anglo-Saxon kings were less worried by money problems than their successors in medieval and modern times, but from Alfred's time maintaining the fleet became a costly business.

In return for the support of his subjects, the king gave them protection and rewarded them with grants of land.

Besides their loyalty to the king, men were also bound by obligations to their own relations: the bond of kinship. If someone were murdered, it was the duty of his relations to avenge him: to die unavenged was a terrible thing. Fear of family vengeance helped to prevent crime at a time when there was no better way of enforcing the law. Everyone had a wergild ('man-price'), the sum payable in compensation to his family by those responsible for his death. Sometimes wergild was refused by the injured family, who preferred violent revenge. Then tremendous feuds began, with one act of vengeance following another. We know of one feud in Northumbria which began in 1016 and was still going strong nearly seventy years later. But kinship also meant cooperation in everything within the clan, looking after orphans, and even protecting the interests of a young woman who married outside the family.

The amount of a man's wergild was a sign of his position in society. A nobleman's wergild was larger than a peasant's.

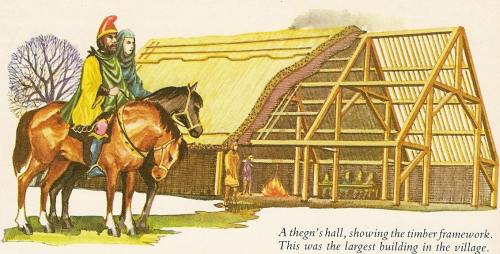

To be classed as a nobleman, or thegn, a man had to have at least five hides of land (a hide was the amount needed to support one household). The nobleman lived in a windowless, barn-like hall, built of wood, surrounded by smaller houses and protected by a stockade. (Stone buildings appeared in the 9th century.) The furniture was simple - trestle tables, benches, and straw mattresses on the floor. In this hall, much heavy drinking and telling of stories took place after a day's hunting. Anglo-Saxon poetry is full of fighting, feasts and falconry - the main activities of the thegns. Before Alfred's time, few could read.

Running the household was the woman's job. But an Anglo-Saxon household was nothing like a suburban semidetached. It was almost self-sufficient, doing its own baking, brewing and so on. The woman's job was not mere housework, more like managing a business. Anglo-Saxon women were not oppressed. Divorce was easy (Christianity made it harder), arid a divorced woman was entitled to half the household goods. She could hold property in her own right-impossible in later times.

Running the household was the woman's job. But an Anglo-Saxon household was nothing like a suburban semidetached. It was almost self-sufficient, doing its own baking, brewing and so on. The woman's job was not mere housework, more like managing a business. Anglo-Saxon women were not oppressed. Divorce was easy (Christianity made it harder), arid a divorced woman was entitled to half the household goods. She could hold property in her own right-impossible in later times.

The wergild of a churl, or peasant, was one-sixth that of a nobleman. The churl normally held at least one hide of land, and lived in a simple thatched hut with no window or chimney - just a hole in the roof. The better kinds of tradesmen - goldsmiths, sword-makers, falconers and small merchants - were also classed as churls. The churl was free but poor, and he depended on the nobleman for protection. In time, he often came to sell his service to the nobleman and so, gradually, he became less independent.

The third class in society was the slave, or unfree peasant. He had no rights and no wergild , though if you killed him you had to pay compensation to his owner (about 1 pound - the price of eight oxen). Unlike the churl, the slaves could often improved his position and even buy his freedom.

Although Anglo-Saxon settlements were nearly self-sufficient, trade in goods like salt, fish and metals went on inside the country and overseas. The contents of the Sutton Hoo burial ship proved that an early East Anglian king owned luxuries imported from Europe. England's chief exports were wool and slaves (although the slave trade declined in Christian times because of Church opposition.) Trade led to towns growing up at harbours and crossing places. London and Winchester were the largest; few others had more than 5,000 people.

Although Anglo-Saxon settlements were nearly self-sufficient, trade in goods like salt, fish and metals went on inside the country and overseas. The contents of the Sutton Hoo burial ship proved that an early East Anglian king owned luxuries imported from Europe. England's chief exports were wool and slaves (although the slave trade declined in Christian times because of Church opposition.) Trade led to towns growing up at harbours and crossing places. London and Winchester were the largest; few others had more than 5,000 people.

Although several kings issued written laws, a lot of Anglo-Saxon law was simply custom, passed on by word of mouth from one generation to the next. There were no professional lawyers, and the nearest thing to a law court was the folk moot, a public assembly where quarrels were settled, local problems discussed and crime punished. (Later, some noblemen had private courts on their own estates.)

An accused man sometimes had to prove his innocence by ordeal. One form of ordeal - probably not so common, though we hear a lot about it in books - was by water. The accused was thrown in, and if he floated he was guilty. The trouble was that if he sank, although he might be proved innocent, he was likely to be drowned. However, not many crimes carried the death penalty. The Church disliked capital punishment, though the alternative it preferred - chopping off a hand or an ear - seems savage enough to us.

The Christian Church in Britain History of Britain (историяБритании)