Топик: The history of Old English and its development

b) indefinite

sum (some),

æ'nig (any) - both behave the same way as strong adjectives

c) negative

nán, næ'nig (no, none) - declined like strong adjectives

d) relative

þe (which, that)

séþe (which, that) - they are not declined

In Proto-Indo-European and in many ancient Indo-European languages there was a special kind of declension calleed pronominal, using only by pronouns and opposed to the one used by nouns, adjectives and numerals. Old English lost it, and its pronouns use all the same endings as the nouns and adjectives. Maybe the only inflection which remembers the Proto-language times, is the neuter nominative -t in hwæt and þæt , the ancient ending for inanimate (inactive) nouns and pronouns.

The Old English Numeral.

It is obvious that all Indo-European languages have the general trend of transformation

from the synthetic (or inflectional) stage to the analytic one. At least for the latest 1,000 years this trend could be observed in all branches of the family. The level of this analitization process in each single language can be estimated by several features, their presence or absence in the language. One of them is for sure the declension of the numerals. In Proto-Indo-European all numerals, both cardinal and ordinal, were declined, as they derived on a very ancient stage from nouns or adjectives, originally being a declined part of speech. There are still language groups within the family with decline their numerals: among them, Slavic and Baltic are the most typical samples. They practically did not suffer any influence of the analytic processes. But all other groups seem to have been influenced somehow. Ancient Italic and Hellenic languages left the declension only for the first four cardinal pronouns (from 1 to 4), the same with ancient Celtic.

The Old English language preserves this system of declension only for three numerals. It is therefore much easier to learn, though not for English speakers I guess - Modern English lacks declension at all.

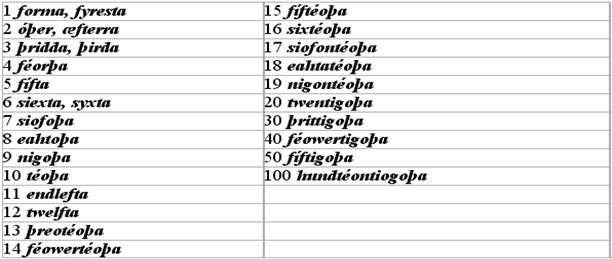

Here is the list of the cardinal numerals:

Ordinal numerals use the suffix -ta or -þa , etymologically a common Indo-European one (*-to- ).

The Old English Adverb.

Adverbs can be either primary (original adverbs) or derive from the adjectives. In fact, adverbs appeared in the language rather late, and eraly Proto-Indo-European did not use them, but later some auxiliary nouns and pronouns losing their declension started to play the role of adverbial modifiers. That's how thew primary adverbs emerged.

In Old English the basic primary adverbs were the following ones:

þa (then)

þonne (then)

þæ'r (there)

þider (thither)

nú (now)

hér (here)

hider (hither)

heonan (hence)

sóna (soon)

oft (often)

eft (again)

swá (so)

hwílum (sometimes).

Secondary adverbs originated from the instrumental singular of the neuter adjectives of strong declension. They all add the suffix -e : wide (widely), déope (deeply), fæste (fast), hearde (hard). Another major sugroup of them used the suffixes -líc, -líce from more complexed adjectives: bealdlíce (boldly), freondlíce (in a friendly way).

Adverbs, as well as adjectives, had their degrees of comparison:

wíde - wídor - wídost (widely - more widely - most widely)

long - leng (long - longer)

feorr (far) - fierr

sófte (softly) - séft

éaþe (easily) - íeþ

wel (well) - betre - best

yfele (badly) - wiers, wyrs - wierst

micele (much) - máre - mæ'st

The Old English Verb.

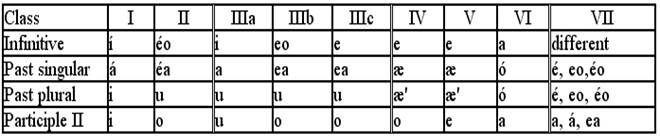

Old English system had strong and weak verbs: the ones which used the ancient Germanic type of conjugation (the Ablaut), and the ones which just added endings to their past and participle forms. Strong verbs make the clear majority. According to the traditional division, which is taken form Gothic and is accepted by modern linguistics, all strong verbs are distinguished between seven classes, each having its peculiarities in conjugation and in the stem structure. It is easy to define which verb is which class, so you will not swear trying to identify the type of conjugation of this or that verb (unlike the situation with the substantives).

Here is the table which is composed for you to see the root vowels of all strong verb classes. Except the VII class, they all have exact stem vowels for all four main forms:

Now let us see what Old English strong verbs of all those seven classes looked like and what were their main four forms. I should mention that besides the vowel changes in the stem, verbal forms also changed stem consonants very often. The rule of such changes is not mentioned practically in any books on the Old English language, though there is some. See for yourselves this little chart where the samples of strong verb classes are given with their four forms:

Infinitive, Past singular, Past plural, Participle II (or Past Participle)

Class I

wrítan (to write), wrát, writon, writen

snípan (to cut), snáþ, snidon, sniden

Other examples: belífan (stay), clífan (cling), ygrípan (clutch), bítan (bite), slítan (slit), besmítan (dirty), gewítan (go), blícan (glitter), sícan (sigh), stígan (mount), scínan (shine), árísan (arise), líþan (go).

Class II

béodan (to offer), béad, budon, boden

céosan (to choose), céas, curon, coren

Other examples: créopan (creep), cléofan (cleave), fléotan (fleet), géotan (pour), gréotan (weep), néotan (enjoy), scéotan (shoot), léogan (lie), bréowan (brew), dréosan (fall), fréosan (freeze), forléosan (lose).

Class III

III a) a nasal consonant

drincan (to drink), dranc, druncon, druncen

Other: swindan (vanish), onginnan (begin), sinnan (reflect), winnan (work), gelimpan (happen), swimman (swim).

III b) l + a consonant

helpan (to help), healp, hulpon, holpen

Other: delfan (delve), swelgan (swallow), sweltan (die), bellan (bark), melcan (milk).

III c) r, h + a consonant

steorfan (to die), stearf, sturfon, storfen

weorþan (to become), wearþ, wurdon, worden

feohtan (to fight), feaht, fuhton, fohten

More: ceorfan (carve), hweorfan (turn), weorpan (throw), beorgan (conceal), beorcan (bark).

Class IV

stelan (to steal), stæ'l, stæ'lon, stolen

beran (to bear), bæ'r, bæ'ron, boren

More: cwelan (die), helan (conceal), teran (tear), brecan (break).

Class V

tredan (to tread), træ'd, træ'don, treden

cweþan (to say), cwæ'þ, cwæ'don, cweden

More: metan (measure), swefan (sleep), wefan (weave), sprecan (to speak), wrecan (persecute), lesan (gather), etan (eat), wesan (be).

Class VI

faran (to go), fór, fóron, faren

More: galan (sing), grafan (dig), hladan (lade), wadan (walk), dragan (drag), gnagan (gnaw), bacan (bake), scacan (shake), wascan (wash).

Class VII

hátan (to call), hét, héton, háten

feallan (to fall), feoll, feollon, feallen

cnéawan (to know), cnéow, cnéowon, cnáwen

More: blondan (blend), ondræ'dan (fear), lácan (jump), scadan (divide), fealdan (fold), healdan (hold), sponnan (span), béatan (beat), blówan (flourish), hlówan (low), spówan (flourish), máwan (mow), sáwan (sow), ráwan (turn).

So the rule from the table above is observed carefully. The VII class was made especially for those verbs which did not fit into any of the six classes. In fact the verbs of the VII class are irregular and cannot be explained by a certain exact rule, though they are quite numerous in the language.

Examining verbs of Old English comparing to those of Modern English it is easy to catch the point of transformation. Not only the ending -an in the infinitive has dropped, but the stems were subject to many changes some of which are not hard to find. For example, the long í in the stem gives i with an open syllable in the modern language (wrítan > write, scínan > shine ). The same can be said about a, which nowadays is a in open syllables pronounced [æ] (hladan > lade ). The initial combination sc turns to sh ; the open e was transformed into ea practically everywhere (sprecan > speak, tredan > tread , etc.). Such laws of transformation which you can gather into a small table help to recreate the Old word from a Modern English one in case you do not have a dictionary in hand, and therefore are important for reconstruction of the languages.