Учебное пособие: Deep Are the Roots A Concise History of Britain

Latin was a language of monasteries, Norman French was now the language of law and authority. Inflected English, spoken differently in the various regions remained the language of the people.

The brightest evidence of the situation in the country was the Domesday Book (1086), a survey of England's land and people; according to it Norman society still rested on "lordship, secular and spiritual, and the King, wise or foolish, was the lord of lords, with only Lord in Heaven and the Saints above him.”

Historians have introduced into their interpretation of Norman and other European lordship the term "feudalism", first employed during the 12th century. The term was used in both narrow and broad sense. Narrowly it was related to military (knightly) service as a condition of tenure of land. Broadly it was related to the tenure of land itself, obligation and dependence, as expressed in the term "vassalage". The first relationship focuses on warfare in an age of violence, the second on the use as well as the tenure of land in an age when land was the key to society.

All land in the country belonged to the Crown. The king was the greatest landowner in the country and he parcelled out (gave away) the land to the great landowners who were his tenants-in-chief (barons). The barons held their land as a gift, in return for specified services to the Crown. When barons parceled out their land, they also required knightly services from their tenants. During the reign of William 1170 barons had in their service about 4000 knights who were distinguishable as a social group.

The two social groups were opposed to "the poor men": lords themselves cultivated only a third or two fifths of the arable land in use. The rest was cultivated by various kinds of "peasants" (a controversial term not in use at that time): villeins (41%), cottagers (32%), free holders (14%) the group holding (20% of the land) and serfs (10%) – the group with no land at all. At the time of the Domesday Book, the basic distinction was, however, that all men are either free (free holders) or serfs.

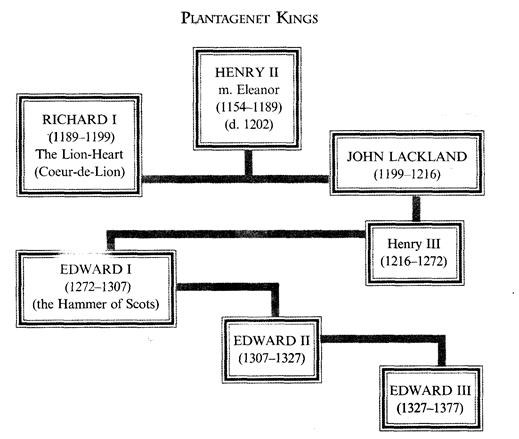

In the 13th century King John (Lackland) (1199-1216) replaced military service of his tenants-in-chief by payments, known as "shield money".

In rural England lords lived in manors which were in their own estates. The peasants, free holders and others lived in villages and hamlets.

The Domesday Book was designed for fiscal purposes to increase and protect the King's revenue.

The full implications of the social, political and cultural changes following the Norman Conquest took time to work themselves out.

They were: a political unification of the country and the centralization of government - a strong royal government, feudal interdependence; the supreme power of the King over all his vassals; the establishment of the feudal hierarchy, a further development of the relationship between the King and the barons, sometimes stormy, sometimes cohesive, an emergence of English common law (from precedent to precedent), the making of Parliament.

The latter two were the most obvious phenomena if we investigate (consider) the historical events chronologically and examine the sequence of monarchs.

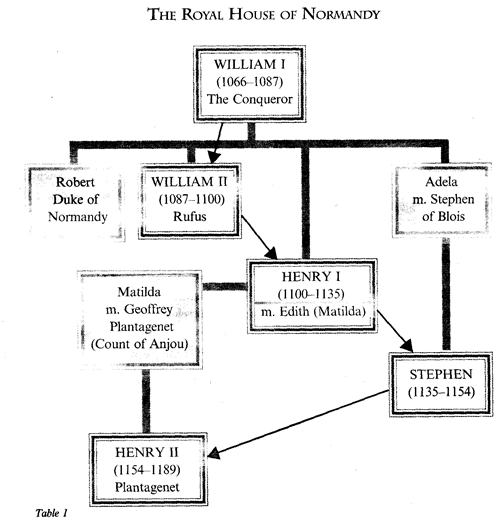

William I The Conqueror (1066-1087) (the Norman Dynasty) died as a result of falling from his horse in a battle in France, was succeeded by his two sons, one after the other:

William II (1087-1100) was cruel but a brave soldier, little loved and little missed when he died.

Henry I (1100-1135) was scholarly and well educated. His daughter was married to the German Emperor Henry V, and later upon his death to Geophrey ofAnjou; the son of Geophrey ofAnjou (Angevin) became the first Plantagenet*.

* Planta genista – Latin for "broom".

Henry II (1154-1189) was friendly with Thomas Becket, a humble clerk, who was appointed the archbishop of Canterbury. Henry misjudged this man who considered his first loyalty to be the Church and not the King.

The conflict ended in the murder of Thomas Becket in his own cathedral by the King's servants. Becket was canonized (St. Thomas); his shrine became a place of pilgrimage for the whole of Europe, for the cures effected there, until it was destroyed by Henry VIII in 1538. So the King of the House of Plantagenet was the first to have a conflict with the Church and he physically destroyed the opposition.

His wife Eleanor took a lively interest in politics. Somewhat too lively at times, for she abetted (helped and supported) her song when they rebelledagainst their father, she was, as a result, imprisoned.

Henry II's reign was one of constitutional progress and territorial expansion.

Richard I the Lion-Heart (1189-1199).

King Richard may have had the heart of a lion but England saw all too little of him. He was called a romantic sportsman and spent most of his life in Crusades in the Holy Land.

He used England's money to finance his crusades and other adventures, but he was not very lucky – returning from his successful mission, he was captured, and was kept imprisoned in Austria, awaiting the payment of a huge ransom.

He returned to England to stop his younger brother John from usurping the throne, soon after, he rushed to fight King Philip of France who had supported John. Philip was defeated but Richard was killed in a siege of a castle.

His wife who never set foot in England, left no children. So, John (Lackland) (1199-1216), the youngest son of King Henry II, continued the dynasty's rule.

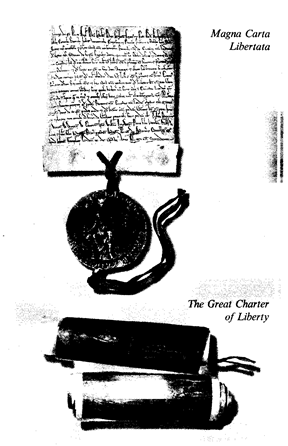

King John Lackland was the most unpopular king: he lost most of his French possessions; he broke his father's heart with his misbehavior, he rebelled against his brother, quarrelled with the Pope, etc. The list of his stupidities and misdemeanours was endless but he did one good thing (or was forced to do it). In 1215 the barons made him seal the Magna Carta, which, though it limited the prerogative of the Crown and extended the powers of the Barons, has since become the foundation stone of an Englishman's liberty.

The pressure on the pocket is more quickly felt than the pressure on the mind - that is why John Lackland was forced by his barons to seal the Magna Carta Libertata (the Great Charter of 1215). Pressed by the demands of war, he had imposed taxes that irritated many of his most powerful subjects. The Magna Carta is a document that dealt with privileges claimed by Norman barons. It was to become part of the English constitutional inheritance, because the baronial claims for liberties were in time translated into the universal language of freedom and justice. It was the beginning of limiting the prerogatives of the Crown.

During the struggle for the Great Charter (Magna Carta) the legions of barons openly opposed the King – disobeyed him, did not pay taxes, raised an army of knights, enjoyed support of townsmen (London supported them), the King was forced to seal the Charter.

It's important to point out that by limiting the King's power, Magna Carta restricted arbitrary actions of barons towards knights and proclaimed the power of law over the free people of the country.

King John was succeeded by his son Henry III (1216-1272). He was not as bad as his father but he was continually short of money and extravagant by nature.