Учебное пособие: Deep Are the Roots A Concise History of Britain

The country was divided into supporters and enemies of the King and a Civil war broke out.

The army of barons was headed (led) by Earl Simon de Montfort and was at first successful in capturing the King's fortresses and castles. They were greeted by townsmen and students of Oxford and church bells.

In 1264 Earl Simon took the King prisoner; in 1265 – Parliament was summoned with "commons" represented in it – two knights from a shire and two merchants from a town.

Prince Edward, Henry's son and heir, (later to succeed Henry as Edward I) rescued Henry. King Henry III managed to defeat Simon de Monfort and killed him in a battle and secured his Crown and his rule.

The 1295 Parliament was called Model Parliament, though it assured a continuity of the 1265 Parliament of Simon de Monfort.

The commons were summoned by the King's Writ to some of the Parliaments (one in eight before 1284; one in three – in the later years of Edward the I's reign, one of which was the so-called Model Parliament of 1295).

The "Oxford Provisions" were not observed by Kings. So, in the 12th and 13th centuries, relationships between the king and the barons, and the making of Parliment were the main historical phenomena of that period.

During the reign of Edward I (1272-1307) there were not only lords, bishops and great abbots present in Parliament, but there were also "commons". This demonstrated the growing wealth and importance of townsmen and knights of the shire not only in the local communities but also in the whole country.

Economics and politics were very closely connected, and the King's main goal in summoning Parliament was to raise money from the population through taxes – 1/10th from people in towns, 1/15th – from the people in the country.

Social relations in the country were undergoing changes in the 13th century. Enforced labour services by villeins were giving way to wage labour, and villeins commuted their labor-dues by paying money to the lord instead. Then the pattern changed: the lords again required labor services. But a lot of villeins were freed, and some of the freed were able, energetic or lucky enough to buy land and prosper as Yomen.

The 13th century was a period of substantial economic activity. Wheat was shipped overseas, but the country's wealth was coming from the exports of wool. Later on, when the wool began to be made into cloth in England, rather than exported as raw material, it stimulated the growth of industry. In the 13th and 14th centuries England was far behind Flanders in the production of cloth but there was enough development.

Questions:

1. What were the peculiar traits of the Norman Rule in England?

2. What was the meaning of the term "feudalism" in relation to Norman England?

3. Why was the Domesday book written?

4. What were the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of the Norman Conquest?

5. When was the first conflict of the King with Church?

6. What do you know about the relations in the family of Henry II?

7. What was the first attempt to limit the power of the King? When was it and why?

8. When did the British Parliament appear and how did it develop in the Middle Ages?

9. What were economic and social relations in the early Middle Ages in England?

Later Middle Ages

Edward I (1272-1307) was determined to strengthen his royal authority and his Kingdom. To do that he asserted his rule in all territories on the British Isles, especially in Wales and Scotland. He succeeded in imposing English rule on Wales: his son, who was born in a Welsh castle and "could spell not a word of English” at that time, later, in 1301 was created the Prince of Wales and ruler of the principality. Since that time the eldest son of the English monarch has been given that title.

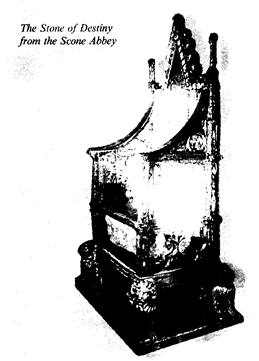

Relationships between England and Scotland were similar to those between England and Wales, but the Scots had a greater degree of independence. Edward I had made several military raids to the Northern kingdom, seized the national treasure – the Stone of Destiny from the Scone Abbey (1296) but had failed to subdue the Scots. Edward I who had been called "the Hammer of Scots" died not far from the border of Scotland during his last abortive campaign to defeat the Scots.

The rule of his son, EdwardII (1307-1327) is traditionally characterized as a great failure of the hereditary principles of Monarchy: Edward II had no talent to be a King, but he was the eldest son and succeeded his father. He angered the barons by his foolishness, his extravagance, favourites and military defeats. His reign was a troubled one and he was deposed and forced to abdicate by the barons, assisted by his wife. He died, probably murdered, and was succeeded by his son, Edward III (1327-1377).

Edward III is recognized by historians as a passionate fighter, who was fond of tournaments, chivalry and battles. He instituted the Order of the Garter and cultivated the spirit of chivalry at his court. He pursued a sensible policy of tolerance with barons, thus securing their loyalty. His commercial policies facilitated the development of wool trade and rise of prosperity. But the warrior king was eager to lead his knights in battles, so Scotland was his first rather hard prey as he had failed to subjugate it, though having taken its King David prisoner to England. The dynastic accident helped Edward III to start the Hundred Years' War (1338-1453) which was carried during the reigns of five English Kings.

Edward declared his claim to the French throne, as his mother had been the sister of Charles IV, king of France, who left no male heir when he died in 1338. This was a respectable enough reason for the war to return the lost English lands in France. The results of the first stage of the war were not as successful as the English had expected them to be. But several victories were won at sea (1340 at Sluys), and in the field– Gascony was recaptured, at Crecy the English archers made the King of France flee from the battle field, Calais after a long siege surrendered in the face of starvation. King Edward's eldest son,– Edward, the Black Prince, a warrior of a high reputation, in 1356 won a victory as Poitiers. In 1348 the outbreak of plague, "the Black death" dealt a terrible blow at the people of Europe and England. It was a terrible disaster, more than 1/3 of the English population died.

The economy and trade of England suffered and the social unrest was spreading due to the results of the economic, social, political and military status. Violence was sparked off by yet another polltax of 1381. People revolted against the tax-collectors and judges, in the south and south-east of England. The rebels, led by Wat Tyler and John Ball, a clergyman, marched to London, captured the Tower with the help of Londoners, killed the archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor. John Ball was a radical opponent of the Church-lords and supported the ideas of John Wycliffe, the first reformer of the Church (1330–1384). He preached ideas of social justice: "When Adam delved and Eve Span who was then the gentleman?"